Thursday, February 28, 2013

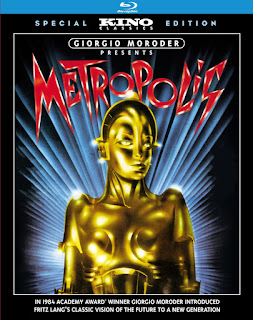

Academy of the Underrated: Giorgio Moroder's Metropolis (1984 release)

Now you may think that I've gone a little crazy. Everyone loves Metropolis, and what's more, I've already reviewed it! But this one needs some context. Composer and producer Giorgio Moroder released a partial restoration of this beloved silent film in 1984, at a time when the only other version was the bastardized US cut. To attract people to theaters, especially the kids who would normally have no interest in silent movies, he released it with a modern electronic rock score similar to the work he did for Scarface, Flashdance, etc., and featuring a number of familiar stars like Freddie Mercury, Pat Benatar, and Bonnie Tyler. Critics welcomed the new footage but scorned the music, and it's long been lambasted as an unnecessary modernizing touch on a timeless classic.

So I'm going to bat for it. I may be incredibly biased, since this was the way I first saw the film, but even then I knew the rock score was a sore point. But it works, and the reason it works is because the film itself is so timeless. It goes just as well with an electronic rock score as it does with its original orchestral accompaniment, and though it's been rendered a curiosity by the discovery of the complete version, it has its own aesthetic appeal.

The plot is more or less the same- a futuristic city divided between elite surface-dwellers and downtrodden workers inhabiting subterranean slums. When Maria (Brigitte Helm) brings a group of worker children to the surface gardens, she catches the eye of Jon Fredersen (Gustav Fröhlich), son of the city master Freder (Alfred Abel), and he follows her back into the depths, where he sees firsthand the cruelty inflicted on the workers. Setting out to make things right, he poses as a worker and finds Maria again, as she hosts sermons counselling the workers that a mediating savior will come. But Freder and the mad inventor Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) also have set eyes on Maria, and under the former's instructions, the scientist kidnaps her and gives his soulless Robotrix the girl's face. The false Maria sows discord among the workers, finally inciting them to revolt and destroy the machines they serve- but they don't realize that doing so will destroy their homes, and their children.

Because a lot of footage was still missing, Moroder searched through photo archives and script materials (including the collection of the film's No. 1 fan, Forrest J. Ackerman), and created a number of bridging scenes using stills and captions. This is the first reconstruction to mention Rotwang's wife Hel, though it leaves out the fact that Rotwang deliberately sends the robot to start a riot and destroy the city as revenge for his wife's death. Oddly enough this is the shortest running of the many versions of the film, because Moroder replaced the dialogue intertitles with subtitles (which does leave out a couple of the more creative title cards).

The result is a movie that really speeds along, and the almost wall-to-wall music score- punctuated with the occasional sound effect- enhances the momentum. The best music in the film is that which is purely orchestral (or rather, part orchestra, part electronica). The main theme is a pulsing, ominous beat accompanied by a sweeping melody which hints at the heroic struggle to come, and Moroder makes some choices which are wonderfully non-obvious; Rotwang's pursuit of Maria is rendered more terrifying by a strangely giddy backing track which suggests the inventor's perverse glee. But the single most effective passage is that which accompanies the False Maria's dance before the elite at Yoshiwara, Metropolis' house of sin. (Unfortunately, these latter two are not available on the film's soundtrack album, and none of the music on the album sounds exactly like it did in the film, due to Moroder's maddening penchant for remixing.)

The vocal performances are a little less consistent- inevitably some of the lyrics are obvious, and the Pat Benatar ballad "Here's My Heart" is too cliché. On the other hand there are some interesting and offbeat entries too, most specifically Cycle V's "Blood From A Stone", the mechanical anthem for the workers. Bonnie Tyler was unfortunately recovering from vocal surgery when she performed "Here She Comes" but her raspy lyrics do have a certain charm.

Despite all the concessions made to modern audiences, this is still very obviously Metropolis, and for years, decades even, it was the best version on the market. (Even when it was off the market, after going out of print on VHS and not hitting DVD until 2011.) Some of the touches- notably the color tinting- aren't out of place for what silent filmmakers were experimenting with, and absolutely none of it compromises the film's spirit or its message. And the music, sounding as science-fiction-y as most of the electronic scores of the era, enhances both the movie's futuristic and gothic sensibilities. I may even prefer it to the original score composed for the movie, even if this version of the film is not quite as satisfying as the full one. So Moroder's Metropolis will always have a place in my heart, and hopefully one in film history, as a work that did a lot to reintroduce silent film to audiences who had never given it a look. It's not the best version, but it has charms of its own.

In conclusion I would like to apologize to all the deaf people who wasted their time reading this.

Screenplay by Thea Von Harbou

Directed by Fritz Lang

Grade: A-

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

Indeed, a great film.

I don't care, except for the "Strobing scene," for "Flashdance."

Post a Comment