Yes, this is normally a space killer, and yes, it is the end of the month, but the passing of composer John Barry, for whom the James Bond series was but one of many notches in a long career, makes this a good time to celebrate some of his work.

Monday, January 31, 2011

Sunday, January 30, 2011

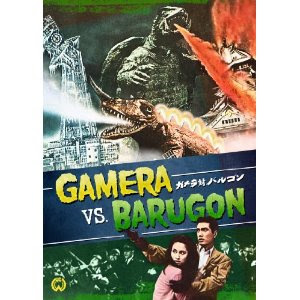

Random Movie Report #85: Gamera vs. Barugon

The Gamera series has always been under appreciated, the poor cousin to the more lavish Godzilla films of the same period (even though their success ended up influencing Toho’s series.) However, the Shout! Factory DVD releases of the classic films are making them look quite a bit better. Viewed in widescreen with quality transfers, they’re not quite as ratty or cheap as they seemed, and GAMERA VS. BARUGON in particular stands out. An unusually dark, serious, and annoying-little-kid-free entry in the series, the first sequel and first full-color monster bout for the jet-powered turtle is a romp which can stand up with some of Toho’s better kaiju epics.

When last we left Gamera, he had been lured into a rocket and fired off to Mars (seriously.) A meteor strikes his capsule, releasing him, and he flies back to Earth, making short work of a dam and heading to a volcano to recharge his flame-powered batteries. Meanwhile, an air pilot named Keisuke (Kojiro Hongo) quits his job to join with a group of men who are planning to retrieve a valuable opal from an area around New Guinea, where Keisuke’s now-disabled brother Ichiro (Akira Natsuki) hid it during the war. Ignoring the warnings of the natives, who insist that the area is cursed, Keisuke, sailor Kawajiri (Yuzo Hayakawa), and criminal Onodera (Koji Fujiyama) recover the strange egg-shaped jewel, only for Onodera to double-cross his friends and run off, keeping the jewel for himself. Kawajiri is killed by a scorpion’s sting, and Keisuke is injured in a cave-in. He is nursed back to health by the natives and a Japanese doctor, none of whom are happy to learn that the jewel has been taken; an oddly light-skinned native, Karen (Kyoko Enami), volunteers to go to Japan with him to try and recover it.

The reason for this is that the jewel is actually the egg of a monster named Barugon, and when Onodera lets it be exposed to the light of an infrared lamp on the voyage back home, it hatches, blowing up the ship and releasing a giant reptilian beast on Osaka. Barugon has quite the diverse arsenal of abilities, with freezing breath, a giant tongue, and a devastating rainbow beam it can project over great distances. Gamera is attracted by the energy the new monster gives off, and the two quickly start to battle it out, but our newly-heroic turtle is frozen and pushed onto his back. It looks like it’s up to the Japanese military, Karen, and a newly repentant Keisuke to find a way of defeating Barugon once and for all.

This is the only film in the original Gamera series not to have any child protagonist, and the tone overall is much darker and more adult than the rest of the series, even the first. I hate to join the “darker is better” crowd, but in this case the approach yields good results; the central story is very strong and I really like the theme of redemption. Keisuke’s venture seems harmless enough at first, but between greed and disrespect for native traditions it’s a venture that’s bound to yield bad results. It helps that Onodera is a genuinely scummy character, at one point leaving Keisuke’s brother and his wife to die helplessly in the path of Barugon’s rampage. Director Shigeo Tanaka brings a nice sordid atmosphere to the human scenes, and Hongo is particularly good at showing his character’s remorse. Chuji Kinoshita’s score also adds to the vaguely oppressive atmosphere.

The downside to such an approach is that Gamera himself does not get a lot of focus; indeed, the fact that he’s basically the good guy goes unremarked-upon. Still, the film doesn’t skimp on monster action, and while some of the effects are a little threadbare, VFX director Noriaki Yuasa does create some imaginative setpieces. It’s genuinely interesting to see the monsters do battle in a frozen cityscape, and Barugon is a wonderfully strange first foe for the equally eccentric jet-powered turtle to confront. The addition of color allows for an interesting trend in the series to surface; Gamera’s battles are a lot bloodier than those of Godzilla or other Toho monsters from around this time, but Yuasa keeps things kid-friendly by giving the monsters bright dishwasher-soap-colored blood.

For whatever reason Daiei decided not to stick with the “mature” approach for the rest of the Gamera movies, leaving this as an unusual but effective change of pace. It’s weirdly touching, and the human story gives us just enough of a connection for the monster action to work that much better. GAMERA VS. BARUGON is probably the best of the original series, and it’s great to see it finally get its due.

Written by Nisan Takahasi

DIrected by Shigeo Tanaka

Grade: B+

Wednesday, January 26, 2011

Frasierquest 3.11: The Friend

Bob: Of course all Texans think they invented barbecue. Arrogant bastards!

Making friends is supposed to be something automatic. We enter a new environment, we make connections, and on those occasions where we don’t it’s a sign that something’s wrong. Frasier has lived in Seattle for years, but he suddenly finds himself very alone, and in trying to remedy that, opens himself up to some very uncomfortable situations. “The Friend” is an episode based around the humor of embarrassment, which can be a dealbreaker for many viewers and has never been my favorite. Still, despite some dated aspects, it speaks to some of the more difficult parts of this necessary human ritual.

When Frasier finds himself in possession of two tickets to a major event, and no-one to share them with, he suddenly realizes that he barely has any friends in Seattle. Against Roz’s advice he puts out a plea for friendship on the air, and after fielding some of the more terrifying responses, decides to meet with a man named Bob (Griffin Dunne). Bob is a genial enough fellow at first, but Frasier doesn’t share his love of barbecue and of long lectures on the proper way to prepare it, nor does he appreciate Bob’s love of bizarre hats or tendency to put finger quotes over everything. They’re just not clicking, and Frasier is about to break things off, as it were, when he sees that Bob is in a wheelchair. In a swoon of excessive liberal guilt he decides to try and tough it out, but as friends go, Bob is clingy.

It’s a sign of progress that Frasier’s trepidation at “breaking up” with Bob solely because he’s in a wheelchair seems odd to most viewers. Daphne, for one, is more enlightened on the subject, having experience working with the handicapped, but Frasier’s just too spineless to risk any insensitivity. His inaction makes things worse, making it harder and harder to disengage. Normally, if you strike up an acquaintance with someone and you find you don’t have a lot in common, it’s easy not to see them very often. But Frasier made this a project and he’s committed to it.

Which is not to say that Bob doesn’t bear any of the blame for how things go wrong. He doesn’t know when to stop, and while that kind of effusive personality can be endearing, it’s no doubt part of what makes it hard for Frasier to connect to him. It’s a good performance by Dunne (who was nominated for an Emmy), which illustrates a certain kind of person we all know, and sometimes we get along with that kind of person and sometimes we find them insufferable. He doesn’t seem to ever pick up on the fact that Frasier isn’t interested in barbecue or funny hats, and perhaps wants to be best buddies right away instead of letting a friendship grow over time. For the most part Frasier is the one in the wrong, as he had a responsibility to end things more gracefully than he does, but there’s a nice complication to the scenario.

Inevitably, the ending is an unhappy one. But Frasier makes an odd sacrifice in trying to spare Bob’s feelings, one which makes the scene much more awkward for the viewer but fits his own conscience. The climax also brings the story’s other major conflict to the fore, which is that Frasier is essentially “dumping” Niles in an attempt to find a best friend who is not his brother. Niles’ jealousy doesn’t directly affect Frasier and Bob’s attempted friendship, but his attempt to “get back” at his brother is amusing.

This is one of those episodes where the humor comes from a fairly painful place, so it’s not one I watch frequently. Still, both the hurt and the humor are rooted in truth; friendship is a difficult business, or at least it can be if we take it seriously. Frasier learns the hard way that you can’t force it, but there’s a nobility in his attempts, as spineless as they are. As bad as loneliness is, there are worse situations. Ones involving hats.

Guest Caller: Armisted Maupin as Gerard

Written by Jack Burditt

Directed by Philip Charles Mackenzie

Aired January 16, 1996

Frasier: Oh, for God's sake, Niles. When we go out to dinner I always know exactly what you're going to say before you say it.

Niles: Well, then I'm sorry you had to hear that, Frasier.

(Quote assistance from Iain McCallum’s transcript at TwizTV.com)

Wednesday, January 19, 2011

Random Movie Report #84: The Complete Metropolis

This one is long overdue. After decades of cheap public domain releases and partial restorations, Fritz Lang’s METROPOLIS was finally released in a more-or-less complete version last year, incorporating footage found in a 16mm print in Argentina. I missed its theatrical tour of the States, but it’s since come out on DVD, and though I waited longer than I needed to, it’s still worth it.

METROPOLIS is arguably the first great science fiction film, though it took a long time for it to be appreciated as such. A massive epic which UFA apparently intended to be the most expensive German film ever (so as to prove their ability to put on a big production and attract foreign investment), it suffered from mixed reactions at first, and later heavy edits and a dramatic reworking of some key points of its storyline. “The Complete Metropolis” is not entirely an accurate term for this latest restoration, as a few scraps of footage are still lost, but those pieces are minor enough that they’ve been bridged with a couple of new captions. In its full form, METROPOLIS stands up better than ever as a work of cinematic art, and one of the defining pictures of the silent era. For all the unlikely twists in the story and the oversimplified social commentary, it’s an amazing spectacle and a beautifully orchestrated drama, one that’s ultimately timeless in its beauty.

Metropolis is the dream city of the future, a mass of towers, lights, and elevated roads, all kept running by massive machines below the surface. These machines are tended to by a slave class of workers, who work themselves often literally to death at their posts, and who are kept separate from the elites in an underground city even further beneath the surface of the Earth. Freder (Gustav Fröhlich), the son of the city’s master Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel), catches sight of the lovely Maria (Brigitte Helm), a worker’s daughter, when she brings a group of the workers’ children to the surface to see their “brothers”. Following her back under, he sees the misery the workers labor in, and becomes determined to change things.

Turning against his father, and enlisting the help of a sacked clerk (Theodor Loos), Freder goes down again, changing places with a worker (Erwin Biswanger). He discovers that Maria is a spiritual leader, urging the workers to be patient for the arrival of a mediator who will act as the heart between the hands that maintain the machines and the brain that runs the city. Freder is willing to step into this role, but Fredersen has seen what Maria can do, and instructs the mad scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) to abduct her and replace her with a duplicate, in the form of a robot Rotwang invented to try and recreate his dead wife. Rotwang has his own plans for the False Maria, though, and intends to use her to bring about the city’s destruction- revenge for Fredersen stealing his wife years ago.

Complicated, ain’t it? Fritz Lang had no aversion to melodrama, but what’s remarkable is how well this flows in the film itself. However crazy the story is, it never becomes overwhelming or hard to follow- Thea Von Harbou’s screenplay moves with a certain linear logic, where every event seems to follow rationally from the last and it’s only when you step back that the whole thing starts to look loopy. Lang’s visual storytelling is superb; like any good epic director, he knows when to cut from the big sweeping vistas to smaller, more intimate moments.

One of the things the new restoration reveals is just how much of an ill-conceived and idiotic hackjob Paramount’s recut of the film was. In the American cut that was most commonly in the public domain, Rotwang and Fredersen’s scheme is to use a robot duplicate of Maria to incite the workers to revolt and destroy themselves so that they can be replaced with an entire force of robots, despite the fact that it’s apparently cost Rotwang years- and the loss of a hand- just to put together the one. This was apparently done because Rotwang’s dead wife’s name is Hel, and the studio thought U.S. audiences might titter at the name on the memorial statue. Moroder’s version restores the Hel element, but makes it seem like the robot Maria simply goes out of control. Finally restoring the element of vengeance restores a thematic pattern, marking Rotwang not as a mere puppet of the establishment but a malevolent heart in mirror to Freder’s benevolent one. This makes it appropriate that the final battle is between the two, over Maria, who is the soul of Metropolis.

The film also restores the rest of a subplot regarding a sinister Man in Black whom Fredersen sends to shadow his son, and who causes many problems for Freder’s nascent resistance movement. A number of scenes with Josaphat and Georgy are restored, rendering their sudden appearances in the film’s third act less surprising. Surprisingly a number of effects shots and setpieces were also clipped, and various incidental parts of scenes put back into place make the pacing feel a lot steadier. The short gaps that still remain seem virtually insignificant- there’s one piece I’d love for somebody to find, but this really does seem like the complete picture.

The film’s spectacle also feels more lavish and real; if the cut METROPOLIS was a series of pretty images, the full version is more of a visit to a fictional place, with lovely details like city newspapers, some good interiors of Yoshiwara, and a brief sequence involving open-door elevators that seems like minor business but must have been a pretty elaborate mechanical trick. There are shots in this film that still seem inexplicable, and the film’s most famous sequence- an accident at the machines that turns into a vision of slaves being sacrificed to a demon-god Moloch- is a breathtaking marriage of dissolves and mattes with full scale sets.

Even though she’s not billed first in the cast, the film belongs to Brigette Helm, who plays an astonishing number of roles; not only the true and false Maria, but the un-disguised robot, the grim reaper, and the planner of the tower of Babel in a story sequence. (She’s also billed as the Seven Deadly Sins, but they all appear together and- yeah this movie is weird.) Helm’s performance may still be the best I’ve seen in a silent film; she has the frenetic physical energy such performances require, but also the conviction needed to sell it. Frölich’s performance as Freder is more maudlin, but the extended cut restores some subtler touches on his part, and Able and Klein-Rogge are both magnificent, especially when sharing the screen.

It’s a funny thing about re-edits. I thought METROPOLIS was a masterpiece before, so the completed version feels less like an improvement than a validation. It’s a film that went from having a few strident defenders to finally being taken seriously as a classic of the form, and its completion is merely the capstone of its ascent. Even the film’s much derided message, that a heart must mediate between the mind and the hands, has a certain naive, idealistic truth to it- Lang does not trust in authority or revolution, but calls always for compassion. Perhaps we will always need that call, and so METROPOLIS will always be timeless.

Screenplay by Thea Von Harbou

Directed by Fritz Lang

Grade: A+

Sunday, January 16, 2011

In Theaters: Black Swan

Audacity and showmanship. These things are, to my mind, what have been most deficient in the film industry as of late, and that’s why I’m particularly grateful for BLACK SWAN. It’s a fine film in its own right, Darren Aronofsky continuing his stellar track record, but it’s also willing to cross the line, and to go so thoroughly into the head of its main character that it ventures into outright surrealism. The film actually isn’t nearly as excessive as other reviews led me to expect- I think the relative realism of most art-house movies has skewed critics’ measures of such things- but it’s still a head trip, and a good one at that.

Natalie Portman is Nina, a ballerina at the New York Met, which is beginning production on SWAN LAKE to close out the season. Nina dreams of being the Swan Queen, but in order to do so she has to dance both the tragic White Swan and the evil, seductive Black Swan- and director Thomas (Vincent Cassell) isn’t sure the disciplined, delicate Nina has the passion for the latter. He unexpectedly gives her the part, but this is just the start of her troubles, for she now has to master the dual role and, in doing so, get in touch with her dark side. She’s not entirely sure she’s secure in the part either, not after a new dancer, Lily (Mila Kunis) shows up displaying all the seductive and smoky attitude that Nina needs. Continued conflicts with her controlling mother (Barbara Hershey) don’t help, and soon she’s picking at a rash on her back and starting to see things that aren’t necessarily there.

This is something of a breakthrough role for Portman. To be sure, the role of a dedicated, studious ingenue with a buttoned-down life is not, on the surface, a big stretch, but the film is told entirely from her point of view; Portman has to carry every single scene, and convey the slow erosion of sanity that the pressure to be perfect inflicts on Nina. Portman handles the big moments and the small gestures equally well, and though she has a very strong cast backing her up (Cassell is wonderfully sleazy), she deserves much of the credit for the film working as well as it does.

To get back to the point of what some other critics have said, I’ve seen excessive melodrama and surrealism that becomes so much stage clutter, and this ain’t that. What makes the downright Cronenbergian images of body horror and transformation work so well is that they’re given the right build-up. The film is aggressively normal in its earliest stages, at times even subdued given the dramatic nature of the material. Of course, this is all relative for people’s various standards of surrealism, but basically I went into this expecting a Dario Argento movie. Which would not have been bad either, but there’s a line and BLACK SWAN doesn’t cross it until it’s good and ready.

It’s interesting to see now how Aronofsky’s films have centered around the concept of obsession. Nina is consumed by the pursuit of artistic perfection, by the challenge of mastering not only the dance but the emotions underlying it. It’s not entirely a challenge of her own making, as her director, her mother, and Lily push and pull at her from many different directions. But while it’s horrible to see her mind put under such a strain, her reasons for doing so are compelling. What sets this apart from the standard pressures-of-showbiz narrative is the emphasis placed on the art itself; Nina isn’t in it for fame or applause, she wants to create something beautiful, but the creation of beauty requires great agony.

Ultimately, Nina’s story is something anyone ever involved with the arts may be able to identify with. It’s a story that’s dark, sometimes unpleasant, but never less than compelling, and Aronofsky brings a tight script to life with remarkable attention to detail. It’s not the sort of film that leaves you easily.

Story by Andres Heinz

Screenplay by Mark Heyman, Andres Heinz, and John McLaughlin

Directed by Darren Aronofsky

Grade: A

Wednesday, January 12, 2011

Frasierquest 3.10: It's Hard To Say Goodbye If You Won't Leave

Kate: You know what? I'm not one of those people for whom "antique" is a verb.

Going into Season 3, I was surprised to find out just how relatively quickly the Kate Costas arc resolves. We’re not even to the halfway point of the season and we’re already at the end, which can’t help but feel abrupt. This is the nature of guest stars on television- they’re only around for so long, especially if they happen to be acclaimed stars of stage and screen with many awards and many offers. Mercedes Ruehl has been fun, but it’s time for her to go, and “It’s Hard To Say Goodbye If You Won’t Leave” serves as a thoughtful exit.

Frasier has a hard time getting his mind off of Kate after their previous trysts. He’s inwardly debating whether to try and make this an actual relationship, despite her apparent lack of interest, and even lets slip to Roz that Kate was indeed the on-air Dirty Girl. Heroically, Roz keeps this a secret. But before Frasier can even begin to pursue Kate, she tells him that she’ll be leaving shortly to take charge of a station in Chicago. This puts Frasier in the position of either having to let her go or make some stupid romantic gesture, and after a couple of minor misunderstandings, he ends up making a mad dash to the airport.

It’s what happens next that’s the important thing in this episode, as Frasier and Kate finally get to discuss having an actual relationship. There are many ways this could have ended, and there’s something very refreshing about the way it does. Frasier and Kate like each other, they have seemingly compatible personalities, but when they compare the details of their lives and desires, they don’t just match up. Frasier wants more children, Kate doesn’t. Kate has a cat, Frasier is allergic. Kate wants to live on a ranch, Frasier in a penthouse. They just can’t fit, and while so many actual relationships end because of this, movies and TV shows tend to avoid this particular downfall for fear of it being undramatic. More often it’s a temporary obstacle on the way to a happy ending, with one party willing to sacrifice their dreams for the other, but neither Frasier or Kate are in a position to give ground.

But while the episode’s resolution is almost perversely anticlimactic, it works surprisingly well. It’s not really sad or unpleasant, there’s just the calm and gentle comedown after heights of romantic tension. It’s almost a relief. Frasier gets to keep the life he’s accustomed to, rather than throw it away; he’s the kind of guy who would like to be able to sacrifice everything for love, but he’s not there yet, and this isn’t quite love anyway.

The only major subplot here is Niles attempting to get used to the bachelor life, hanging out at Frasier’s apartment and testing the patience of Martin and Daphne ever so slightly. His being there does prompt a discussion on the story of CASABLANCA, and I’m honestly not sure how Niles hasn’t had that ending (nay, half the story) spoiled yet. I’m sure such things are possible, but it seems uncultured of him not to have seen the picture before now. We also get THE WAY WE WERE spoiled, but somehow I care less about that.

Since this episode is the last to feature Kate Costas, it’s time to look back over the arc. The five episodes are an example of decompressed storytelling compared to how FRASIER normally moves; their relationship isn’t jammed into one or two episodes, which allows it to rise and fall more organically at the expense of there not being as much happening in each individual episode. The pacing is not entirely there- “Leapin’ Lizards” is really a placeholder- but overall we’re left with a satisfying story. It’s a mature, adult romance where sometimes things don’t work out and it’s not anyone’s fault.

So while it’s been frustrating trying to write substantive pieces on episodes that are just parts of a larger whole, to the extent that my complaining about it is probably a cliché by now, I can’t say this little experiment in long-form storytelling has been anything but a good thing. Not only is Kate a good character and fun to watch with Frasier, she’s something that right off the bat made Season 3 different. Recurring guest stars are going to pop up more often, as will new story arcs, and while FRASIER will always be episodic, there’s evolution taking place.

No Guest Caller

Written by Steven Levitan

Directed by Philip Charles Mackenzie

Aired January 9, 1996

Martin: Grow up you two! I'm just saying it's perfectly natural. I can't tell you the number of times I was on a stake-out in the cold picturing your mother in front of a warm fire wearing nothing but a...

Frasier/Niles: DAD!!!

Martin: Oh, I'm sorry. One day your mother and I went on a church picnic and the two of you came floating down the river in little wicker baskets!

Niles: Was that so hard?

Quotes by Iain McCallum at TwizTV.com

Saturday, January 08, 2011

My Favorite Movies: Brazil

BRAZIL is one of my favorite movies, one I love so much that years ago I begged my way into a screening when I found myself out of cash. (Still not proud of that.) It’s a film that, often going in, I don’t feel I’m prepared for, because it’s a dark and heavy experience; however, it’s also an exhilarating and cathartic one. BRAZIL is hard to describe; the magnum opus of visionary director Terry Gilliam, it’s known almost as much for the initial controversy surrounding its release as for the actual picture.

It’s possibly a science fiction film, though it doesn’t take place in the future or concentrate on technology per se. It’s obviously a dystopia, but without the political or sociological focus with which such things are normally put together. It’s a jet-black comedy, but with a little more heart than usual. It’s a vision of all the horror and insanity of our world, filtered into an alternate reality. However BRAZIL defies genre and description, it’s one of the very best films of its time.

The film takes place “Somewhere in the 20th Century”, in a messy, overbuilt Art Deco world run by an overgrown bureaucracy and besieged by constant terrorist bombings. A dead fly falling into a government computer causes a warrant intended for a man named Tuttle to be placed for a man named Buttle, who is arrested, and dies during a brutal interrogation. The Ministry of Information’s attempts to cover all this up ensnare records clerk Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce), the humble son of a wealthy widow (Katherine Helmond) who’s constantly getting her face redone. Sam has a rich dream life, seeing himself as an angel flying to the rescue of a beautiful woman, and in the course of trying to get a refund check to Buttle’s wife he catches sight of Jill Layton (Kim Griest), a trucker who lives above the Buttles, and a dead ringer for his dream girl. Obsessed, he tries to track Jill down, and since she’s been making noise about Buttle being falsely arrested, she’s now in real danger and he feels compelled to try and save her.

While most dystopias like to draw a clear indication of what went wrong, and whatever alarming social trend was taken to its ultimate extreme, BRAZIL’s world defies easy political labeling. There’s a huge central government which runs everything inefficiently, a Tea Party nightmare, but also an aggressive consumer culture and a downright Dickensian division of classes. Technology is everywhere, but it’s creaking, retrograde technology- computers with monitors so small they need magnifying lenses to be properly read, clacking teletype machines, pneumatic tube systems, and ducts in every room like the guts of a living organism. One starts to get the feeling that the world of BRAZIL, like our own, cannot trace its ailments down to one bad decision or even a series of them, but simply the worst of human nature. It’s all the insanity and banal evil that we encounter in everyday life, amplified and given a new context so that it becomes universal, like THE PRISONER’s Village. It’s a staggering creation, beautiful in a sick way.

The title of the film refers to a familiar old song, which is used as a leitmotif throughout. It represents the desire to escape, and the fantasy of doing so, which is always out of reach. Sam Lowry is a dreamer, for better and for worse; his romantic fantasies about Jill only make things worse when he tries to translate them into reality, drawing attention to them both and jeopardizing her subtler plans of resistance. Despite his idealistic visions, Sam is a cog in an evil system, and defying it is not something he’s used to. But for all his missteps and awkward moments we like Sam, and empathize with him; this is partly down to Jonathan Pryce being terrific (it’s odd that he has so rarely played “everyman” parts), but also because his imperfections are ours. We’re never as good or virtuous or heroic as we want to be, but we keep dreaming. Everyone in this film engages in some kind of escape at some point, from Jill watching the Marx Brothers to a roomful of thuggish guards singing Christmas carols.

A similar ambiguity exists for the true rebel in the system, Harry Tuttle, as played by Robert De Niro; a rogue heating repairman, he does the jobs that take Central Services forever to do, but in helping Sam, he inconveniences him later. CS- as represented by two rude mechanicals played by Bob Hoskins and Derrick O’ Connor- eventually gets to Sam’s apartment, discovers the scab work, and tears the place apart in a revengeful act of repair. Tuttle’s heroism doesn’t seem to make much of a difference to the system overall.

While Sam’s fantasies are a liability for him, the film doesn’t make much of a case for rationality either. Had Sam not gone after Jill, the system would still have sought to eliminate her, and her logical approach of trying to report a wrongful arrest would get her killed. Buttle would still be dead- the great injustice has already happened, and everything else is collateral damage. There are a few times where Sam, a whiz with computers and savvy to how at least some parts of the system works, tries some very logical techniques to accomplish his goals, but the system always finds a way to fight back. Dreaming is no solution to the problems of reality, but neither is reason; it’s a chaotic world, and the film’s rambling, chaotic feel reinforces that. The film doesn’t offer a solution, as such; it’s a despairing picture in some ways, but the anger and sadness are tinged with a wistful quality that borders on outright sentiment.

A word about the editing. There are a few different versions of the film, but fortunately you’re unlikely to come across studio head Sid Sheinberg’s “Love Conquers All” re-edit unless you specifically watch it as part of the Criterion boxed set of the film. The American, original international, and final Director’s cuts of the film all retain Gilliam’s basic vision, but have a number of minor differences and subtle tonal shifts. The Director’s Cut takes the best of both worlds for the most part, though I mourn the loss of a truly hilarious line at the end of the scene where Sam first visits his mother.

We dream, ere we die; ultimately, Terry Gilliam’s work is about our need to fantasize, not because it actually fixes anything in this broken world of ours, not even because it might actually help us, but because we can’t help it. Despite the sadness of the film’s message, it’s a thrilling experience, a white-hot jet of rage at all the pointless and horrible things we encounter in our lives. It’s realized with remarkable craftsmanship, from the stunning visual design to a superb music score by the great Michael Kamen (an extract of which was the go-to movie trailer music for a few years). The cast sparkles, and the dialogue is laden with all sorts of clever word-twisting. Though not quite perfect in any of its incarnations, BRAZIL is a masterpiece and one of the greatest films of its time and genre. Now if we could only work out what specific genre it’s in.

Written by Terry Gilliam, Tom Stoppard, and Charles McKeown

Directed by Terry Gilliam

Grade: A+

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)